Technologies of language, race + state

an essay-annotation by josh babcock

Also in this section: Origins of the Archive | Contributors | Reading List + Other Resources

“It’s important, therefore, to know who the real enemy is, and to know the function, the very serious function of racism, which is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining over and over again, your reason for being. Somebody says you have no language and so you spend 20 years proving that you do. Somebody says your head isn’t shaped properly so you have scientists working on the fact that it is. Somebody says you have no art so you dredge that up. Somebody says that you have no kingdoms and so you dredge that up. None of that is necessary. There will always be one more thing.”

Toni Morrison, “A Humanist View,” May 30, 1975. From Portland State University’s Oregon Public Speakers Collection, Black Studies Center public dialogue, pt. 2.

introduction

We start from the premise that race, language, and the state are intimately entangled with one another. We further acknowledge that technologies mediate our knowledge of race, language, and the state. Technologies are also mediated by race, language, and the state.

But here, we already need to add nuance to avoid a misunderstanding: race, language, and the state are not identical or reducible to one another, nor are they straightforwardly separable from other forms of difference. When we interact with and encounter others, we also locate them along lines of class, gender, sexuality, ability, education, citizenship, migration histories, settler status, religion, culture, and more. And yet, following Toni Morrison, when we ask questions like, “But is this really about race? Is this really about language” we create a distraction. We place the burden of proof on the critic/analyst to convince us on the terms that we set, rather than trying to understand and advance the necessary work of combating racism as it intersects with other injustices.

Instead, we ought to ask questions like, “How is this [phenomenon, system, structure, interaction, etc.] shaped by race in addition to and in combination with other things? And what are those other things?”

Toward a Raciolinguistic-Technological Perspective

Race isn’t just about observable differences among bodies, a perspective that analysts refer to as phenotype. Race is a technology. So is language. They’re tools, or codes, for making sense of the world, for explaining and making sense of our encounters with difference—but also tools or codes for simplifying how we encounter difference. Our perceptions of difference are profoundly shaped by history: histories of defining, parsing, justifying, narrating, studying, producing policies, and designing technologies to measure phenomena and processes in the world in ways that assume that language and race are something that exist outside us, that preexist our encounters with (and as) real, embodied individuals. When we do this, we must actively disavow and/or passively forget the fact that we only ever encounter raciolinguistic difference in real, embodied individuals.

And yet, our encounters with real, embodied individuals are never as straightforward as we might like to think. Our encounters are structured by our assumptions about what really matters, about what it is that we’re actually responding to through perception, the things we see, the things we hear, the things we know (or assume we know based on clothing, body language, accent, choice of language, etc.): facts of migration, ancestry, religion, class status, educational background. These assumptions aren’t always explicit, though sometimes they are. The assumptions that we make are structured hierarchically, yet flexibly. In the U.S., for instance, we might see someone that we assume is white—until we hear them speak Spanish. An encounter with language might make us change our minds about race (but not necessarily).

Or consider a different case: in Singapore, one person approaches another and speaks Mandarin. The first speaker encounters their interlocutor as a racialized subject, and this guided their language-use. They could be wrong, either about who they’ve taken their interlocutor to be, or about their interlocutor’s language competencies. The same is true for any place. Our raciolinguistic assumptions work as often as they don’t, and yet the repeated failures of our assumptions rarely lead us to abandon those assumptions—about language, race, and their intersectional interconnections with one another and with other vectors of difference.

Equally important, we need to recognize that our habits of perception are not only, or even primarily, about the things we perceive. Instead, we need to focus our attention on the perceiver: who perceives what, and how? Whose habits of perception are assumed to be natural, self-evident, objective, correct? Who or what get perceived, how, and with what effects? Are some speakers judged to be illegitimate language-users or assigned to a lower position in a racial, socioeconomic, or class hierarchy?

“A former Apple employee who noted that he was ‘not Black or Hispanic’ described his experience on a team that was developing speech recognition for Siri…As they worked on different English dialects—Australian, Singaporean, and Indian English—he asked his boss: ‘What about African American English?’ To this his boss responded: ‘Well, Apple products are for the premium market.’”

Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code, Polity 2019, p. 28.

Race isn’t separate from language, the state, or technologies, and yet it has an insidious way of predominating over other technologies, or codes, through which we experience the world. As linguistic anthropologist Jonathan Rosa and education scholar Nelson Flores have argued, when it comes to race, some interpretive practices come to dominate others. Specifically, what they call the “racialized semiotics of white perceiving subjects” come to be equated with reality (Rosa and Flores 2017, 629). Individuals aspire to occupy the position of a white perceiving subject position regardless of the race they identify as, or are identified as by others. The people who aspire to occupy white perceiving subject positions get to attribute their own biases and interpretations to the people they evaluate, categorize, and judge. Importantly, this is about interpretive practices, not about the essential racialized identities that immutably follow the individuals who bear and are judged by them. Whiteness is something that we do, not something that we have.

Jokes aren’t as funny once they’re over-explained, but: the question of where someone is “from” quickly becomes a source of frustration and exclusion depending how narrowly the boundaries of raciolinguistic and national belonging get constructed. It stands in for and collapses a range of assumptions about who can be from a place, and what kinds of places one can be from.

As political scientist, sociologist, and African American Studies scholar Barnor Hesse has argued, “[r]ace is not in the eye of the beholder or in the body of the objectified.” It is “an inherited western, modern-colonial practice of violence, assemblage, superordination, exploitation, and segregation” (Hesse 2016, viii). And racialized colonial distinctions are not just projected onto individual bodies: they are also “recursively remapped within and across nation-state settings” (Rosa and Flores 2017, 636).

Tracking Raciolinguistic State Effects

Here again, the state enters the picture. Scientists, policymakers, politicians, and non-experts in various domains convince themselves and one another that the state needs to concern itself with language, and in particular, that standard languages in order to function efficiently. States construct institutions that police the bounds of standard languages, and invite people to police the language-use of others. Experts construct grammars, dictionaries, canons, and pedagogies that serve as “objective” standards against which to judge and police others (Heller and McElhinny 2017, 106). Speakers learn to experience their own and others’ language as wrong, as bad, as laughable when it deviates from the norms prescribed by linguistic technologies like grammars, dictionaries, canons, pedagogies, etc. These technical solutions are designed to “fix” the so-called deficiency of subjects who do not invest in or readily subject themselves to the state’s standardizing project. Needless to say, as the sociologist Ruha Benjamin has argued, “the road to inequity is paved with technical fixes” (Benjamin 2019, 7).

When we talk about the state, we’re not just talking about national governments. As anthropologist and historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot argues, the state is known and knowable through its effects in the world (Trouillot 2001, 126). Many of these effects are not created by official state institutions, government actors, or politicians, even if they are indirectly authorized or backed by them: for example, “there are many tech insiders hiding behind the language of free speech, allowing racist and sexist harassment to run rampant in the digital public square and looking the other way as avowedly bad actors deliberately crash into others with reckless abandon. For this reason, we should consider how private industry choices are in fact public policy decisions” (Benjamin 2019, 12).

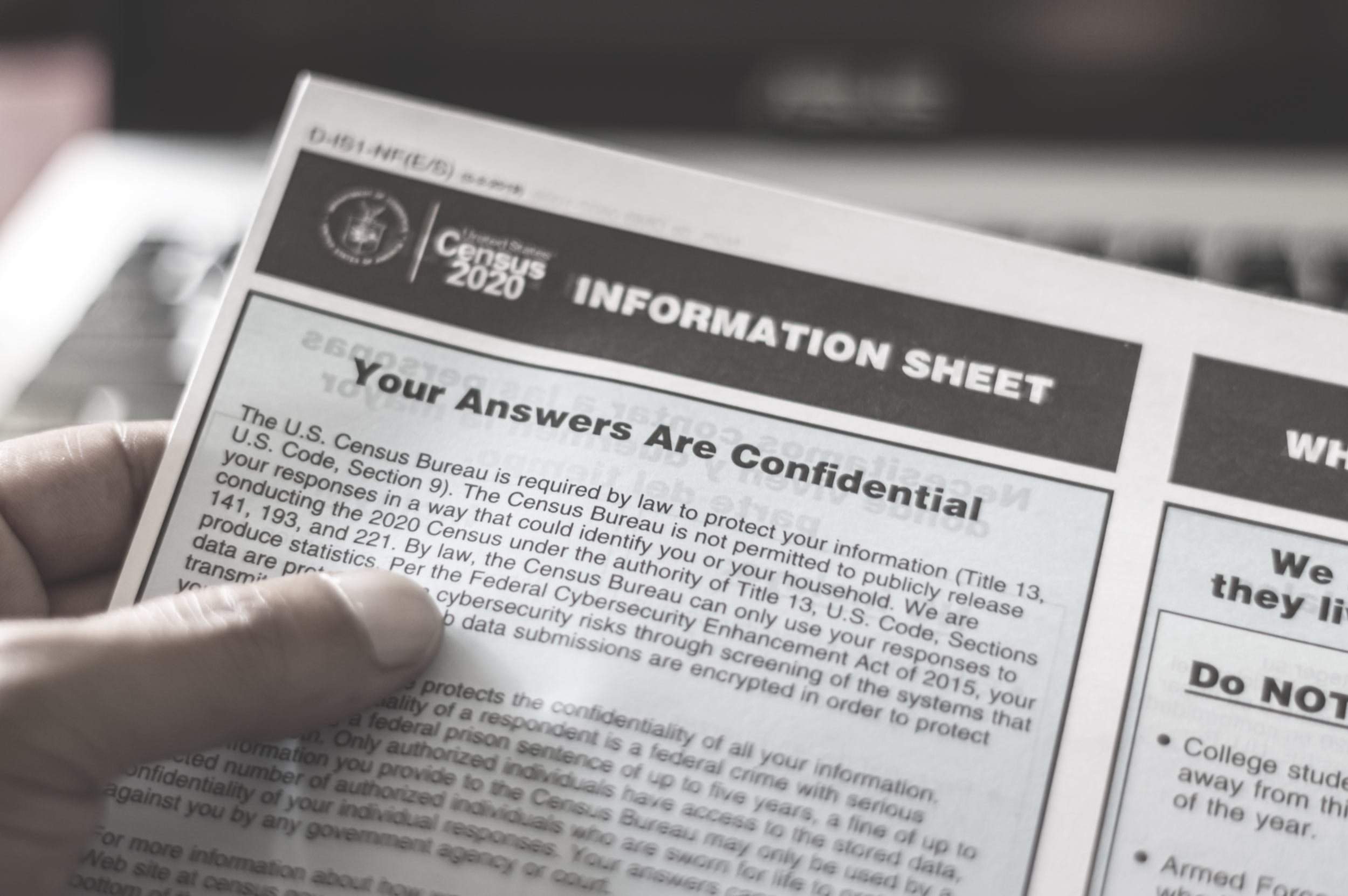

You may rightly be thinking here of private prisons and “security forces” that turn the dehumanization and criminalization of Black and Brown people into both a commodity and an “objective,” scientific “fact” (to paraphrase the complex, multifaceted history discussed by Khalil Gibran Muhammad [2010]), or global “development” programs that have locked the developing world into a near-permanent state of financial vassalage to their past and present colonizers in the Global North (Benjamin 2019, 39). But state effects can also be far more banal: singing a national anthem to open a private sporting event; selecting language preferences on a new smart phone or computer by choosing from a limited, preset list of “national” languages; selling one’s biometric data in exchange for genetic assessments that map race selectively onto sovereign state territories to determine medical risk—to name just a few examples.

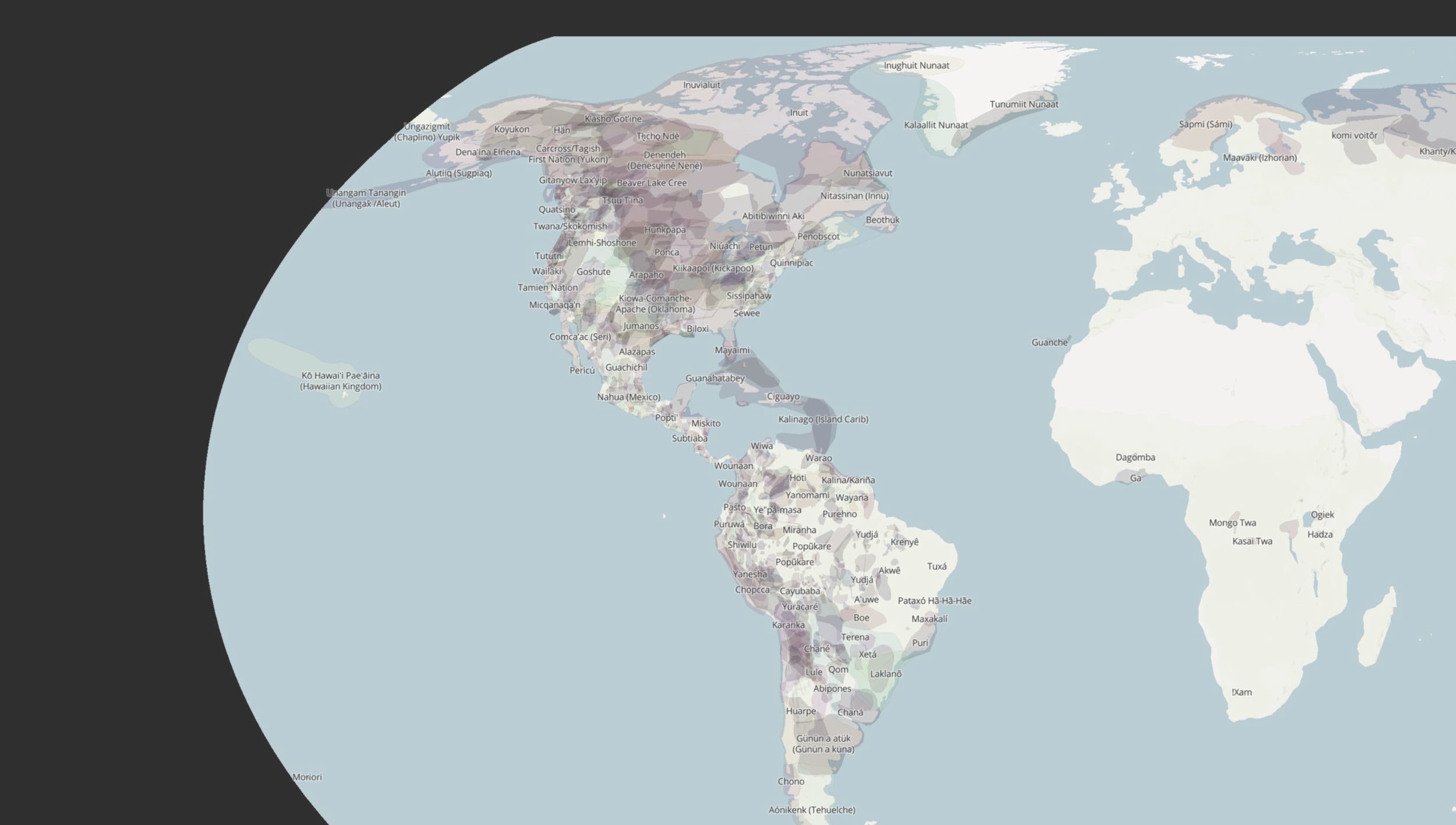

From The Decolonial Atlas on Facebook: “Everyone around the world needs the same lifesaving tools. But a zero-sum mind-set among nationalists and world leaders is jeopardizing access for all. Borders are the scars of intolerance carved into the Earth. #AbolishBorders #NoBorders”

This Is About Us

It’s hard to focus on systems rather than individuals. Further, once we learn to focus on systems, it’s easy to forget that this is about us: it’s about how we act, how we relate to others, how we speak, and how we think. We use language and other technologies to communicate, to convey information, to describe the world, to describe ourselves, but we also use it to talk about race, language, the state, and technology, to both implicitly orient toward the categories that we use to structure our experience, and to explicitly tell ourselves (and one another) stories about why those categories are necessary, natural, or independent of the ways we use them.

It’s true that we must use categories to navigate the world. In many ways they’re inescapable and valuable—at least in some forms. Yet categories do not exist outside us, either as individuals or as people living in community with other people, people who use categories to interpret the world around us in flexible, context-dependent ways.

We’ve created a world of borders, of boundaries, of rigid lines that divide us from people we assume are radically different from us, impossible to understand, frightening or dangerous or less human than we are. We’ve created it; we can also refuse to recreate it any longer. I end this essay with the words of ethnographer, photographer, writer, and educator Nurul H. Rashid on the interrelationships between classification, storytelling, and annotation. The words that I’ve written in this essay are just an annotation to the words, stories, texts, experiences, and knowledges that have been produced by others, which you can find grouped under the archive’s Themes. Through these words, stories, texts, experiences, and knowledges, we can begin to imagine new and different worlds (see the map of Native Lands, below, for a picture of the world that doesn’t involve discrete boundaries). But to learn from and engage with them, we must also unlearn. The fragments that we’ve assembled in this intersectional archive are just one small step in this direction.

“That soft tango between methods of classification and storytelling has always intrigued me as one cannot do without the other. In thinking about the ways we approach knowledge and information, I would often distinguish the two: the former being like air, found everywhere, eddying into breaths that utter space, stories, sayang; the latter, a documented form, a book that can be transmitted to the masses. Whilst both knowledge and information can be easily subjected to both classification and storytelling, its point of encounter resides in different domains. Pairing storytelling alongside classification ensures we do not reify categories of ‘race’, ‘other’, ‘orient’, ‘native’, ‘wild’, created to cast outliers from a perceived centre. Stories allow for ways of correcting categories, as interludes that open boundaries of the geographical, spiritual, mental. It reminds us that, like air, many flow from crevices of memory and ancestry, residing in tongues and limbs who mimic their words, but who might be met with ‘unknown’ when forced into classification. The importance of infusing storytelling into and against classification has thus become the approach undertaken in this attempt to document the nusantara, a space, stories, sayang that many feel on their skin, but have not the words to speak into form. Annotating thus became my way of breathing air alongside the fragments.”

Nurul H. Rashid, “Notes on Annotating,” Pulau Something, 2020.