Themes

Identities reclaimed / Appropriated

How can individuals and groups reclaim and reshape identities—especially when features of those identities have been appropriated by states, state-like actors, and others?

We follow linguistic anthropologist Jonathan Rosa and education scholar Nelson Flores in exploring the ways that people contest racial and linguistic power formations, especially in cases where they seek to transform structural inequality, not just institute a new status quo.

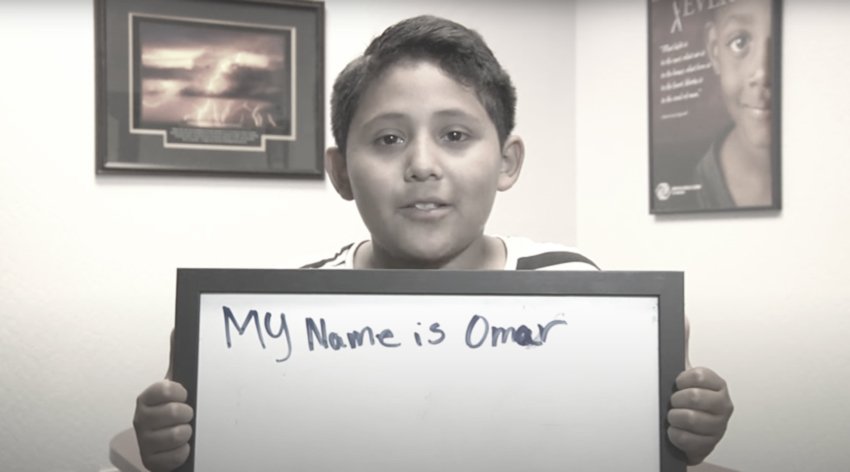

My Name, My Identity

Washoe County School District, 29 June 2016

Ayomide Badmus: This video was produced by a school district in Nevada. It compiles one-on-one interactions / interviews with the school kids talking about their names, answering the question “how did your name come to be.” The video shows how significant personal names are in creating and legitimating identities. For a different perspective, you can also check out this research paper on the naming practices of African American and African immigrant groups in the U.S. as a form of “historical and ethnographic documentation.”

@YassifyBot Regrets Being @YassifyBot

Paper, 24 Nov 2021

Teddy Sandler: As a Twitter trend, Yassificaction drew me in as an example of both queer expression and digital drag. Anyone can download Faceapp and use the Yassify filter, but this article pokes at the potential harm of the filter. Specifically, the appropriation of Yassification by the mainstream can threaten queerness. If it no longer pushes back on conventional beauty standards, it risks becoming a mere tokenization of queerness. Though I fear that, like many queer aesthetics, the trend will eventually get fully adopted into the mainstream, I am glad that the account leading the trend is thinking about this. It will be interesting to see what happens to Yassification, whether it will continue in new forms or simply disappear, overtaken by other similar trends.

Omar Offendum, released 4 July 2010

Marya Tawam: This song by Omar Offendum is based on an Arabic translation of the Langston Hughes poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” Omar Offendum is a Syrian American poet and rapper. I find his poetry inspirational because this was the first Arabic poetry that was accessible to me. Upon hearing this song for the first time, my ears immediately perked up, having never experienced being sung to in a different language and understanding it. It felt as though Omar was speaking to me specifically.

When I found out that the lyrics were translated from Langston Hughes’s poem, I initially wanted to do more research on what the poem “meant.” However, I instead tried first to experience the two different versions on their own terms, understanding the different yet co-operating layers across the works. While both poems take their subject to be the narrator, the English version referring to the narrator directly with “I”. While the Arabic narrator also refers to himself in the first person, the grammar makes the reference less direct, adding a suffix to the verb that indicates who the subject is rather than using a specific word for “I.” After reading Langston Hughes’s poem, I read Offendum’s poem more introspectively, thinking of myself knowing rivers, my own soul growing deep like those rivers.

Sofia Torriente: This photo of me and my dad is a personal memento, evocative yet incomplete. Artifacts like these are a jumping-off point for stories and conversations, whether the associated memory is charged in a positive or a negative way.

Multiplying Demographic Categories/Identities

“The American multiracial and Brazilian black movements have identified the census as a vehicle for their larger political ambition: to refigure and reconstitute racial identities through categorization…

Rather than simply organizing on the basis of a shared and widely assumed identity, what these two movements are shaping is a discourse about identity. Their tactics and strategies may have been influenced by political and institutional changes, but their motivations are derived in part from prevailing racial discourse and their desire to change it. Multiracial activists in the United States seek to challenge the mutual exclusivity and conceptual coherence of existing racial categories (both in society and on the census) by advancing the idea of mulitraciality. This multiracial discourse gives content to a multiracial identity. Similarly, in Brazil, black activists attempt to disrupt the commensurability between images of whiteness, national identity, and racial harmony by advocating for the idea of distinct races instead of one mixed Brazilian race…As these activists rightly see it, the censuses that have upheld ideas of distinct races in the United States and of one mixed race in Brazil can also be used to undermine those ideas.”

Melissa Nobles, Shades of Citizenship: Race and the Census in Modern Politics. Stanford University Press 2001, pp. 21–22.

From the Annotator: Political scientist Melissa Nobles’ comparative social and institutional history of race in the U.S. and Brazilian censuses demonstrates the possibilities and pitfalls that follow from efforts at achieving recognition from existing state institutional structures. Groups’ efforts at contesting racial and linguistic power formations (Rosa and Flores 2017, 637–641) can continue to uphold and normalize the raciolinguistic status quo by multiplying the categories by which reality is institutionally represented and collectively imagined. In other words, adding new categories to the census doesn’t automatically undo the perceived necessity of racial, linguistic, and other kinds of borders, nor does it challenge the logic of categorization itself or transform the inequities that get produced and reproduced by policing the borders between categories. (–Josh Babcock)